an essay in one act

Pray you, love, remember.

~ Ophelia, Hamlet Act IV, Scene V

Characters

The Man

The Boy

Time and Place

Evening, a darkened room lit by a lone lamp on a table or a dresser, maybe a braided rug at center-stage, a rocking chair in a corner, a few stuffed animals or toy trucks off to the side, but nothing clear, nothing resolving fully from shadow.

Now the man, standing by the lamp, clicks it off, and the shadows deepen, the only illumination the light fading through the curtains in the back of the room, the curtains a pale green or a translucent blue—any color, really, which gathers the last light—and the man slowly crosses the room and sits on the floor, leaning up against the boy’s small bed.

The boy crawls out of bed then—he is only five, but tall, substantial, one of those who seems perpetually older than he is, his surprising boyishness delighting and frustrating in equal measure—and sits on the man’s lap, and the man wraps his arms around him, and the boy, wearing for pajamas an old t-shirt that hangs to his knees, curls up as well as he can in the man’s lap and is still, facing the audience.

Light slowly illuminates the boy’s face, and for the evening shadows this is the first time either of the character’s faces has clarified. While the man looks stage right, out over the boy’s head, the boy continues to look at the audience—stares, really, as children do, his face serious, intent, unapologetic.

The Boy: But how does the baby get inside the mom’s tummy?

The Man: Well, bud, now—.

The Boy: (Interrupting, insistent) And how do we die? I mean, we’re alive and then we just die. How is that?

The light shifts here, the angle lengthening through the curtained window in the back. The boy’s face, however, remains sharp and clear. Perhaps, too, there should be some rising nighttime sound: the sighs of an old house, the susurrus of a city, a gentle wind worrying the windows.

The Man: (Stroking the boy’s head, his voice slow, careful) Gosh, bud, you’re full of questions tonight.

The Boy: Like grandfather from the pictures. I mean, how did he just die? He was alive, right?

The Man: Yes.

The Boy: And now he’s dead?

The Man: Yes.

The Boy: What about when he was alive?

The Man: When he was alive? (Here the boy turns to look stage right, his face profiled and shadowed, as the man’s was, and the man turns and faces the audience, the light rounding and softening his features) When he was alive…well, when he was alive he took me once to town. We lived a long way out in the country—.

The Boy: Like a hundred miles?

The Man: Yes, like a hundred miles. It took us two hours to get to town. We were in the old Ford pickup and had a load of culled ewes in the back. I remember we had the radio on to a country station—KGHL Classic Country, I remember that—and the windows were down, and I watched how your grandfather hooked his arm out the open window, and I tried to do the same, though I was too small and had to stretch a long way and after a while I let my arm drop back into my lap. Your grandfather drove us to the stockyards, which were along the river, and we backed up to the chute and unloaded the ewes. The stockyards smelled of manure and straw, and the yard was busy with trucks and pickups and the bleats of sheep and cattle. And after that we went out for a hamburger and—.

The Boy: Was it a hamburger or a cheeseburger?

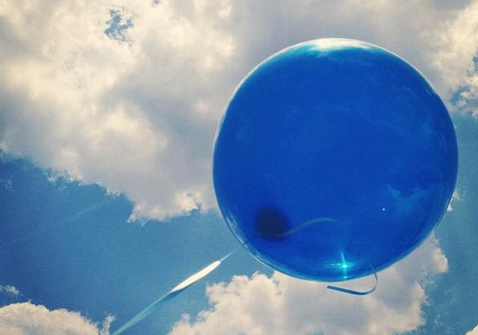

The Man: A cheeseburger. I imagine it was a cheeseburger. Yes, we ate cheeseburgers at the Kit-Kat Cafe, and somewhere your grandfather bought me a helium ballon. I don’t know where. I can’t imagine they sold balloons at the stockyards. Or the cafe. But I had balloon. A bright blue one. And living so far out in the country I hadn’t had many balloons as a boy, at least helium ones that floated. It was in the truck with us as we drove back the way we came, back through town, though when we stopped at the grocery store—there was an IGA we always stopped at—I accidentally let the balloon go. I remember it lifting into the sky, which was gray and white and blue—all those colors at once—but the balloon was only one color, was only blue, and it drifted up above us, over the parking lot and into the sky.

The Boy: Did you cry?

The Man: Yes, I did.

The Boy: Was grandfather sad?

The Man: I don’t know. Maybe he was. Maybe he wasn’t. That trip to town is one of the only things I remember about him. (Here, the two switch once more, the man looking stage right, the boy staring at the audience) I mean, he died when I was only nine. I didn’t know him. Not really.

The Boy: (The boy ‘s face twists) But I’m only five, and I know you—you’re my dad, and he was your dad, and what do you mean you didn’t know him? I don’t understand. What do you mean, Dad? What do you mean?

The boy tries to pull away from the man, to sit up in the man’s lap and look at him, but the man holds the boy all the more tightly, almost too tightly. Eventually, the boy quits struggling and looks back at the audience, his face a knot of worry and fear.

The Man: I don’t know. I’m sorry. Maybe you’re right. Maybe I knew him then but not later. Yes, maybe I knew him then and have only forgotten about knowing him because it’s true he came to me, there in the parking lot, and knelt down so I could look right at him, even though I was so much smaller—he was tall and big across the shoulders and had curly hair, like you do, though his was black, very black—and he knelt down like I never remember him and told me my balloon would float up and up and someday come down and another little boy would catch it and that little boy would be my friend.

The Boy: (The boy’s eyes go wide, a shocked smile breaking across his face. He moves his hands now as he talks) And did it? Did it come down? The balloon? Did the other little boy bring it to you? Was he your friend, like grandfather said? Did you play trucks? What was his favorite color? Was it red? Was it blue like you? Did you climb a tree together one time and decide never to come down?

The boy waits a moment, and when there is no answer—the man still staring off stage right —the boy settles back against the man’s chest and smiles.

The Boy: I bet you did. I bet the two of you were friends. Just like grandfather said.

The light shifts again, and dims, the shadows fading into the blackness, and the wind rises outside the house in earnest now, and for a time we hear only the wind. The boy closes his eyes. Opens them. Closes them again.

The Boy: What else did grandfather say?

The Man: (A thin wire in the man’s voice—of grief, anger?) I don’t remember.

The Boy: Yes, you do.

The Man: No, I don’t.

The Boy: (Eyes still closed) Well, I do.

The Man: (Incredulous) You do?

The Boy: Yes.

The Man: Tell me then.

The Boy: (Yawning) He said, he said…

The boy’s voice fades into the sound of the wind, only to rise again.

The Boy: Grandfather said, See the birds, see the birds. They were up there with the balloon.

Again, the boy pauses, the wind rushing in.

The Boy: Grandfather was saying, he was telling the story, tell me the story…

His head heavy against the man’s chest, the boy drifts in that liminal space—the world both world and dream. The man isn’t crying, not yet, but he seems to tremble, as if any moment the whole of him might spill. And the room fades. The window, the lamp, the rug, even the bed—all disappear into shadow, though a sourceless light rises beneath the man and the boy, as if they have indeed entered another world, as if they fly now through the dark, as if through the boy’s insistence the man finally remembers, can indeed feel his father’s hand on his small shoulder, can sight along the clean line of his father’s up- stretched arm and see the circling birds, black and together shifting against the sky, shifting with the sudden, severe grace of birds.

The Boy: …about when we were birds.

Joe Wilkins is the author of a memoir, The Mountain and the Fathers: Growing up on the Big Dry, winner of the 2014 GLCA New Writers Award and a finalist for the 2013 Orion Book Award, and two collections of poems, Notes from the Journey Westward and Killing the Murnion Dogs. His third full-length collection, When We Were Birds, part of the Miller Williams Series, edited by Billy Collins, now out from the University of Arkansas Press. A Pushcart Prize winner and National Magazine Award finalist, he lives with his wife, son, and daughter in western Oregon, where he teaches writing at Linfield College.