“A letter from America was waiting for me at school this morning, from Mom, saying that Gram Krosschell had died.” This was an entry in my journal on March 22, 1976, in Chungmu-si, South Korea.

“A letter from America was waiting for me at school this morning, from Mom, saying that Gram Krosschell had died.” This was an entry in my journal on March 22, 1976, in Chungmu-si, South Korea.

I don’t remember receiving that letter. It was a long time ago. But I can reconstruct how that moment would have played, because all of my days that first year of Peace Corps were much the same:

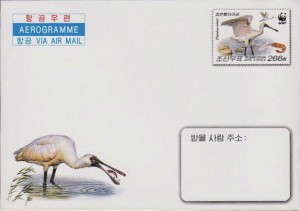

I come into the teachers’ room from a class, and the sky-blue aerogram is peeking out of my letter box. I take it to my desk and sit down in my chair. We wait a moment, letter and I, objects of wonder and furtive curiosity among the teachers as usual. The room is big and open and cold, crammed with some 30 desks, and the one coal stove does not sufficiently heat any of us except the vice-principal occupying the position of power next to it. I slit open the aerogram. I am an English teacher in a boys’ middle school, in a seaside city on the sapphire waters of the Korea Strait. My grandmother had died 19 days before, in a small white house on the dry plains of Minnesota. At the desk next to mine my co-teacher asks “what wrong is.”

That week I recorded in my journal all kinds of semi-mature thoughts about family, distance, “the touch of a hand and a small tearful smile,” the inevitability of death. I wrote then that her death hit me hard, but the words I used betray their essential sentimentality. Perhaps it was the lag in time and distance and maturity, or perhaps just the efficient flimsiness of the aerogram, its one-piece construction, its precise folds and panels, its “additional writing space” on the back that I myself so seldom used in my own letters back home — perhaps the whole ephemeral thing itself was the excuse to conduct business as usual. My grandmother wasn’t young anymore, she was 77, dead of the flu, of all things, and I was 26, and so many worlds separated us that the only real thing I would find to write about in my journal was celebrating her eternal good humor.

***

“Two weeks ago my last grandparent was buried. Gram died Saturday, June 4 of massive cancer that had spread through her gall bladder and liver.” This was my journal entry from June 21, 1977, in Seoul, South Korea.

I assume this death too was announced by aerogram. By then I was in Seoul, in the big distracting city, preparing to train a new group of Peace Corps volunteers, and I have so little recollection of the day’s actual circumstances that I can’t even make them up. But this death was expected, was indeed somewhat blunted by expectation.

I had said goodbye to her two years before, just before leaving the States for Korea. She was convalescing in my parents’ bedroom after her heart attack, and she had death color in her face as she cried with me and implored me to remember the Lord so that we could meet in heaven.

Once again, time and distance would play their part, as did the aerogram, I’m sure, but my writing in the journal this time seems less naive. I said Gram was a strong and complex woman, and I knew her relations to her seven children had sparked an infinite range of love and hate, often simultaneously, but to her young grandchildren she inspired only respect and pleasure, and by this time I had had almost two years of living overseas, and I felt like an adult writing more profoundly about cancer as a retribution for our chemical world (“a gruesome troll gnawing away,” at the end “killing quickly, with utmost pain”), and how life sometimes seems a terrible mix of relief and joy, grief and love.

***

I’m not one to dwell on the past. I spent more than two years in Korea as a Peace Corps Volunteer and hardly ever think about that time anymore. Nor is this some paean to the art of writing letters. The aerogram was small, and if you wrote big enough, you could fulfill your weekly (monthly by the end) obligation of news to your parents and grandmothers in about 10 minutes each. I didn’t save any of the letters I received (my mother saved all the ones I sent and left them with me on a recent visit). But now those letters flutter through memory, like blue patches of sky on a stormy day, weighing almost nothing then, weighing heavily now.

Aerograms aren’t used anymore (although the Post Office reports it still had stock as late as 2006). When my daughters lived overseas recently, my wife and I skyped and texted and had only the problem of distance to worry about, not time. But this week I wish that aerograms were still available. I wish for time, for that two or three weeks’ gap. Our technologies don’t allow it; what I need to tell my family must be told immediately. They must hear it in real time, my wife first as she listens to my side of the doctor’s call, then our older daughter just home from Denmark, then our younger daughter in California, then my mother in Virginia, and as I hold the telephone, and hear their hellos and then the breaths in-taken and the silences and the weak, suppressed cries, I wish for a piece of blue sky, flying over time and distance, inscribed as if on tablets, a proper herald of mortality. I wish to write it down for them, as if the cancer were a foreign country I could visit, then leave.

Jim Krosschell divides his time between Massachusetts and the coast of Maine, where he leads the Coastal Mountains Land Trust and writes “One Man’s Maine.” Read his essay in Contrary, “Yellow Finches.”